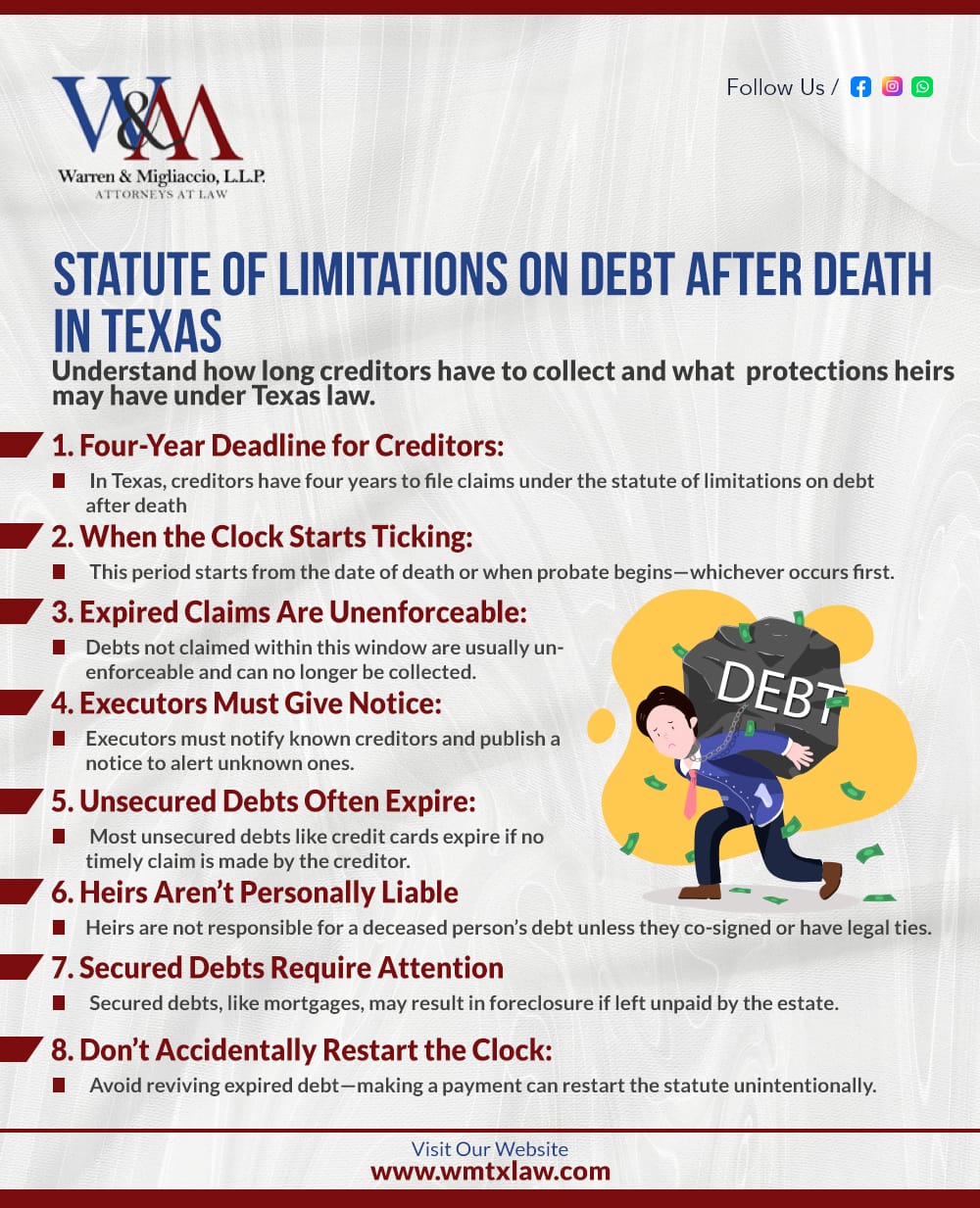

Sorting out a loved one’s debts after they die can feel overwhelming. In Texas, the statute of limitations for collecting most debts after someone’s death is four years from the original due date, during which creditors can seek payment from the deceased’s estate.

This gives creditors a limited window to pursue payment through the estate. That’s a crucial detail for families and executors trying to make sense of what comes next.

If you’re managing an estate or just worried about debt claims, it helps to know unsecured debts like credit cards fall under this time frame. Texas law is pretty strict—if the four-year limit runs out, creditors usually can’t take legal action to collect.

For a closer look at how this works, the Texas State Law Library’s guide on time-barred debts is a good place to start.

Key Takeaways

- Creditors in Texas have four years to collect most debts after someone dies.

- Unsecured debts, like credit cards, are handled during this period in probate.

- Heirs aren’t usually responsible once the statute of limitations ends.

Understanding the Statute of Limitations on Debt After Death in Texas

Texas law lays out a clear timeline for creditors to collect debts after someone passes away. The statute of limitations, probate code, and the kind of debt all play a role in what happens next.

Overview of Statute of Limitations and SOL

The statute of limitations (SOL) is the time creditors have to sue and collect a debt. In Texas, this time limit is usually four years.

If a creditor tries to collect after four years, the debt is considered time-barred. Creditors must act within this window, whether the debtor is alive or not. When someone dies, potential creditors find out through a ‘Notice of Death’ published in a local newspaper. This allows them to assess and claim any outstanding debts within the legally defined timeframe.

This time limit protects the estate from old or questionable claims. If the deadline is missed, courts typically won’t support the collection effort.

If you’re an executor or family member handling an estate, keep this deadline in mind. Most unsecured debts, like credit cards or medical bills, follow the four-year rule under Texas law.

When Time Is On Your Side: A Statute of Limitations Story

Maria was a widow who was worried about her late husband’s credit card debt. Six years after he passed away, debt collectors called her about a $12,000 debt. They told her she had to pay because she was his spouse.

Maria showed me the account statements. I noticed the last payment was made over five years ago. I explained that in Texas, there’s a four-year statute of limitations on credit card debt after death. This meant the debt collectors could not legally ask her for money.

We sent a letter to the debt collectors, citing the specific statute. The calls stopped immediately. Maria was relieved. She had been losing sleep over debt that was no longer her problem. This four-year rule protects families from old debts and helps them move on.

Relevant Texas Law and Probate Code

The Texas Probate Code and related laws outline how to handle debts and claims during probate. During this process, the executor lists the debts and allows creditors to file claims within a set period.

These laws guide executors and families through a step-by-step process. The code ensures they settle estates fairly instead of getting weighed down by old debts. To find out exactly when a debt becomes uncollectible, check the statute of limitations.

Common Types of Debt Affected

Most debts after someone dies are unsecured. These include credit cards, medical bills, and personal loans. In Texas, these debts have a four-year statute of limitations.

- If you make a payment on a debt, it can reset the statute of limitations. This gives creditors more time to collect the remaining balance.

- Secured debts, like mortgages or car loans, are different. Lenders can foreclose or repossess property tied to the debt. They still need to follow legal timelines.

Family members usually don’t have to pay the deceased person’s debts. The estate pays these debts. For more information, check out this Texas guide.

Process of Debt Collection After a Debtor’s Death

After someone dies in Texas, there’s a set process for collecting unpaid debts. Understanding the debt collection process is crucial to effectively manage and settle debts with collectors. This process protects both creditors and the estate.

Notifying Creditors and Filing Creditor Claims

The executor or personal representative must notify creditors about the death. For secured creditors, notice goes out by certified or registered mail within two months of receiving letters testamentary.

Executors are required to post public notices to inform creditors of the death, allowing creditors a specific timeframe to make claims against the estate before they lose their right to collect debts. Unsecured creditors get notified by a newspaper notice. Creditors usually have six months from the executor’s appointment, or four months from when they get notice, to file a claim.

If a creditor doesn’t claim in time, they may lose the right to collect. These deadlines matter a lot for protecting the estate. More on the timeline for creditor claims.

Role of the Executor and Personal Representatives

The executor manages the estate’s debts and assets. It is the estate’s obligation to pay creditors, not the personal responsibility of family members. Their main job is to review and pay valid creditor claims as required by Texas law.

They gather info on all debts, send out required notices, and make sure only valid, timely claims get paid. Invalid or late claims can be rejected. Executors need to keep detailed records of payments and outstanding debts, starting as soon as they get those letters testamentary.

Administration of the Estate

Once creditors submit their claims, the estate administration process determines the payment order. The estate typically uses the deceased’s assets to pay any outstanding debts. Secured debts, such as mortgages or car notes, take priority because they’re tied to specific assets.

Unsecured debts follow after. The estate pays debts from available assets, sometimes needing to sell property. If there’s not enough money, state law sets the order for paying claims.

The executor has to settle valid debts before heirs get any inheritance. You’ll find more on this in the guide on managing debts and estate administration.

Types of Debts and Their Statutes of Limitations

Different debts in Texas come with different statutes of limitations. The rules depend on whether the debt’s secured or unsecured, and the type of agreement.

Secured vs. Unsecured Debts

Secured debts back themselves with collateral, like a house or car. Unsecured debts don’t have any backing—credit cards and medical bills fall into this category.

When someone dies, secured creditors can often claim the collateral if the debt’s unpaid. Unsecured creditors must file a claim with the estate and might not get paid if there aren’t enough assets.

The statute of limitations for most debts, especially unsecured ones, is four years in Texas. That’s four years to sue for repayment.

Credit Cards, Mortgages, and Promissory Notes

For credit cards, Texas gives creditors four years from the last payment or charge to sue. When a debtor dies, debts do not automatically disappear and may be pursued against the deceased’s estate. Wait too long, and the debt becomes “time-barred”—no lawsuit allowed. More on this in the legal guide.

Mortgages are secured debts. If payments stop, lenders can foreclose, but they usually have four years to act after a death.

Promissory notes—written promises to repay—also have a four-year limit for lawsuits, starting at default or nonpayment.

Tax Liens and Child Support

Tax liens are government claims for unpaid taxes and don’t work like regular consumer debts. They can last for years and sometimes don’t expire until paid. Federal and state tax liens follow their own set of rules.

Child support debts stick around even after death and last longer than most debts. Texas law lets people collect past-due child support from an estate—there’s no regular statute of limitations on owed child support once it’s due.

Oral Agreements and Written Contracts

Oral agreements are handshake deals—nothing in writing. In Texas, the statute of limitations is generally four years for oral contracts. If someone dies still owing, creditors need to move fast since these are tough to prove.

Written contracts cover most loans and documented promises. They also get a four-year statute of limitations. Creditors have to show the contract or proof if they claim against the estate. For more, see this Texas law help article.

Probate Proceedings and the Settlement of Debts

Probate is the legal process where a court reviews and settles a deceased person’s estate, including their debts. The estate handles outstanding debts before distributing any inheritance. Texas offers different types of probate, and the handling of debts depends on the type of probate and whether there’s a will.

Probate and Court Approval

Paying most debts during probate needs court approval, especially if it’s a dependent administration. The executor or administrator submits claims to the court, which decides if they’re valid. Creditor-estate disputes are sorted out here, and creditors have to meet certain filing deadlines.

Some small or simple estates might qualify for a shorter probate, but most still need some oversight. Once the court approves, the executor pays allowed debts from estate funds before heirs get anything.

Step | Description |

|---|---|

Submit Claims | Creditors file claims for debts owed |

Court Review | Court checks the claims for validity |

Payment of Debts | Allowed debts are paid from estate assets |

Distribution | Remaining assets go to heirs or beneficiaries |

Dependent vs. Independent Administrations

Texas has two types of estate administrations: dependent and independent. These affect how debts are managed after someone’s death.

Dependent Administration:

- The court oversees almost everything.

- Administrators need court approval to pay debts, sell assets, and resolve claims.

- This offers extra protection but can be slow and costly.

Independent Administration:

- Gives the executor more control.

- Once appointed by the court, the executor can pay debts and manage assets with less oversight.

- Most wills in Texas prefer this method because it’s faster and simpler for families.

For both types, creditors must follow strict timelines to file claims. If they miss the deadline, they may lose the chance to collect. The Texas probate clearly outline these rules.

Testacy and Intestacy Implications

If someone dies with a will (testacy), the will names an executor and might say how debts should be paid. The executor often gets independent powers to settle debts and distribute assets.

Without a will (intestacy), a court-appointed administrator takes over. This process is more controlled by the court, especially if there are disagreements or tricky debts. The court uses Texas law to decide who gets what after debts are handled.

Estate debts always get settled before heirs receive property. Whether there’s a will or not, debts come first. The amount of court involvement depends on the administration type and if there’s a will. For more, see the Texas Law Help estate debts guide.

Creditor Actions and Legal Remedies

Creditors in Texas have a few ways to try collecting debts from an estate after someone dies. Creditors must adhere to the statutory time period, which refers to the legal deadlines for collecting debts or filing legal actions. What they can do depends on the debt type, liens, and the probate process.

Filing Lawsuits and Seeking Judicial Relief

Creditors generally get four years in Texas to file a lawsuit against the estate for unpaid debts. That’s the statute of limitations on debt collection. Understanding the debt collection process is crucial to effectively manage and settle debts with collectors.

After a death, creditors have to act within this period. If they don’t, the court usually won’t allow the claim. The estate’s representative notifies creditors, who then need to present their claims in probate court.

Creditors might seek judicial relief by filing a claim in probate. If the court accepts the claim, they could get a judgment for what’s owed. That judgment lets them pursue estate assets or proceeds from property sales.

Enforcement of Liens and Preferred Debt

Some debts—like mortgages or certain taxes—come with a lien on property. These secured debts get priority over other claims.

Estate property includes various assets that Texas law may protect from debt collection through legal exemptions, such as family allowances and specific protections for surviving family members after someone passes away. A lien allows a creditor to claim the property to recover unpaid debt. In Texas, creditors with preferred debt and lien status receive payment from the sale of the secured property before most other debts. For example, a mortgage lender gets paid first from the proceeds of a home sale.

If there’s money left after paying the lien, it goes back to the estate. If the property’s worth less than the debt, the creditor might chase the rest from other estate assets.

Nonjudicial and Judicial Foreclosures

Foreclosure is common for debts secured by real estate. Texas allows both nonjudicial and judicial foreclosure methods.

Nonjudicial foreclosure skips court. The creditor follows deed of trust steps, including proper notice. It’s typically faster and less expensive.

Judicial foreclosure comes into play if there are questions about the debt or competing claims. The creditor files a lawsuit and needs a court order to sell the property to pay the debt.

In either case, the sale pays off the debt first. Anything left goes back to the estate for heirs or other creditors. More on the foreclosure process in Texas estates is in the law guidelines.

Key Statutes and Procedural Provisions in Texas

Texas law spells out the rules for creditors who want to collect after someone dies. Staying informed about debt collection laws and rights is crucial to effectively navigate interactions with debt collectors and avoid potential legal pitfalls. There are specific Estates Code sections, recent legislative changes, and careful steps for creditors to follow during probate.

Section 146 and Section 294(d) of the Estates Code

Section 146 of the Texas Estates Code tells creditors how to file claims against an estate. Dealing with debt after the death of a loved one is a complex process that involves understanding state laws and the probate process. Creditors must give written notice to the estate’s representative.

Section 294(d) covers when claims can be paid and how to resolve disputes. It protects estate assets from invalid or time-barred claims by setting a payment order—funeral costs, legal fees, taxes, then other claims.

Both sections protect the estate by setting limits and procedures for handling debts.

Recent Legislative Updates: SB 1198

SB 1198 updated probate procedures in Texas, clarifying how debt claims are handled after death. In the nine community property states, debts incurred during marriage can legally transfer to the surviving spouse. The bill aimed to make probate steps clearer and improve communication with creditors.

One big change is clearer guidance on how to notify the estate and what to include in claims. This helps estate reps respond and courts sort valid from invalid debts. SB 1198 also reaffirmed the four-year statute of limitations, matching Texas law.

These updates help both creditors and estate representatives navigate probate cases.

Procedural Requirements for Debt Collection

Creditors must follow certain steps to collect after death. First, they file a claim with probate court or the estate’s administrator, including all documentation.

Quick notice matters—a four-year statute of limitations from the original due date applies in Texas. Miss deadlines or skip paperwork, and the claim might get rejected.

Estate reps have tools to dispute claims, so following the process is crucial for creditors hoping to collect.

Heirs, Inheritance, and Liability for Debts

When someone dies in Texas, debts left behind can make heirs and next of kin nervous. Surviving family members may have legal responsibilities regarding the deceased’s debt, which can vary by state. The law sets out who’s responsible and how debts affect the inheritance process.

Heirs’ and Next of Kin’s Responsibilities

Heirs and next of kin are not personally responsible for a deceased person’s debts. Debts get paid from estate assets before anything passes to heirs. Surviving family members often face challenges in dealing with the debts of deceased relatives, but they are typically not liable unless they have co-signed on the debt or live in a community property state.

If an heir or family member signed or co-signed a loan, they might still owe that specific debt. Joint credit cards or loans can obligate both people.

If the estate can’t cover all debts, some creditors just won’t get paid. Heirs only get what’s left after debts and expenses. In Texas, heirs are only at risk for debts in rare cases, like shared accounts. More on this at Texas Law Help.

Impact on Inheritance and Estate Administration

The estate administration process makes sure debts are paid before heirs get assets. The decedent’s estate plays a crucial role in managing debts after a person’s death. The executor or administrator notifies creditors and pays valid debts with estate funds.

Texas’s four-year statute of limitations applies to many debts. Debts not claimed in time might not get paid, letting heirs keep more. For the specifics, see the Texas statute of limitations for estate debts.

If the estate’s value can’t cover all debts, heirs may receive nothing. Property that passes outside of probate—such as life insurance or retirement accounts with named beneficiaries—typically isn’t used to pay estate debts.

Liability and Consumer Protections

Heirs have important consumer protections under Texas law. Debt collectors can’t harass or mislead family members about liability. While the executor handles payments from the estate, they are not personally liable for those debts unless they fail to manage the estate funds correctly.

Regulations shield grieving families from aggressive collectors. If contacted, heirs should get accurate info about liability, and collectors must follow fair debt collection laws. See the Ross & Shoalmire article for more.

Additional Considerations in Texas Debt Settlement

Some legal rules can change how long creditors have to collect. Debts continue after a person’s death, and creditors have the ability to collect outstanding debts from a deceased individual’s estate. Attorney fees, voluntary payments, and real estate or probate rules can also affect how debt is handled after death.

Tolling of Statute of Limitations

In Texas, the usual statute of limitations for debts is four years. Tolling means this clock can pause for certain reasons—like if a debtor leaves the state or files bankruptcy.

The debtor’s death can also pause or shift the statute clock. For example, a probate claim can change the timeline. Creditors have to file within strict periods after notice from the estate, not just within the regular statute of limitations. These overlapping deadlines can get confusing, so it’s important for heirs and creditors to understand how probate and debt laws interact. More info is at the Texas State Law Library.

Attorney’s Fees and Voluntary Payment

Attorney fees can increase what’s owed in Texas debt cases. Some contracts or laws let creditors collect reasonable legal fees if they sue and win.

Voluntary payments matter too. If someone makes a payment—even on an old debt close to the time limit—the statute of limitations might restart. So, a single payment could give creditors more time to sue. It’s smart to think twice before making promises or payments on old debts, since it can change legal rights and timelines.

Real Estate, Probate and Trust Law Relevance

When someone dies, debts don’t just disappear. Real estate and other probate assets might be used to pay debts. The executor or administrator has to notify creditors and let them make claims—Texas probate law sets the deadlines and steps.

Sometimes property is in a trust or passes outside probate, which can shield it from most debts. Still, creditors may have limited rights to claim certain assets. The Texas Law Help guide breaks down how real estate, probate, and trust law interact with creditor claims and deadlines.

Frequently Asked Questions

Statute of Limitations Basics

What is the statute of limitations on debt after death in Texas?

In Texas, the statute of limitations for most debts after a person’s death is four years from the original due date.

This applies to common unsecured debts like:

Credit card balances

Personal loans

Creditors have only this limited period to file claims against the estate of the decedent.

Responsibility for Debts

Who is responsible for paying a deceased person’s debts in Texas?

The deceased person’s estate assets are responsible for paying valid debts, not individual family members.

The executor or personal representative manages payments using available funds, following Texas probate law’s priority order:

Funeral expenses and costs of administration

Claims of the state and federal government

Secured debts and liens

Credit agreement obligations like credit cards

Any remaining claims

What happens if the estate can’t pay all debts in Texas?

If a deceased person’s estate lacks enough assets to cover outstanding debts, some creditors may not receive payment.

Priority order for payment:

Funeral expenses first

Administration costs next

Secured debts, like mortgages

Unsecured debts, such as credit cards

Partial or no payment:

If there isn’t enough money after higher-priority debts, lower-priority creditors might receive partial payment or nothing at all.

Exempt and Protected Assets

Can creditors take life insurance or retirement accounts to pay debts in Texas?

Generally, life insurance proceeds and most qualified retirement accounts are safe from creditors. They pass directly to beneficiaries instead of probate.

Life Insurance: Paid directly to the named beneficiary. Not part of the estate.

Retirement Accounts: Go to the listed beneficiaries.

Multiple-Party Accounts: Joint or beneficiary-designated accounts usually avoid probate too.

What assets are protected from creditors after death in Texas?

Texas law protects certain assets, including:

Life insurance proceeds with named beneficiaries

Retirement accounts with designated beneficiaries

Homestead property for a surviving spouse or minor children

Certain personal property up to statutory limits

Assets held in properly structured trusts

Debt Collection Rules

Can debt collectors contact family members about a deceased relative’s debts?

Under the FDCPA, debt collectors may only contact:

The executor of the estate

The personal representative

The surviving spouse

They cannot contact other family members about the debt.

If contacted, family members should give the collector the executor’s or probate attorney’s contact details.

Types of Debt and Limitations

What types of debt are subject to the statute of limitations after death?

Different debts have varying statutes of limitations in Texas:

Credit card balances and medical bills: 4 years from default

Personal loans and promissory notes: 4 years from default

Mortgage debt: 4 years to foreclose (though lien remains)

Federal student loans: Discharged upon death

Tax debts: Varies by type (state vs. federal)

Hire purchase agreements: 4 years from default

Summary

When someone passes away in Texas, their debts don’t automatically disappear. However, creditors must claim most unsecured debts—such as credit cards and personal loans—within four years of the person’s death. This legal time frame, known as the statute of limitations, bars collection efforts once it expires and typically renders the debts uncollectible.

The estate’s executor plays a key role in notifying creditors and managing payments using estate assets. Knowing these rules can help families avoid unnecessary stress and navigate probate with greater peace of mind.

Our experienced estate planning attorneys in Texas are ready to help you create an estate plan that meets your needs and goals. During a consultation, we can discuss your situation, answer your legal questions, and discuss how we can help you. Call us at (888) 584-9614 or contact us online to start planning your estate today.